In the quiet heart of Évora, deep in Portugal’s Alentejo region, stands a small chapel that can silence even the most talkative traveller. From the outside, the Capela dos Ossos—Chapel of Bones—looks modest, its whitewashed walls and arched doorway blending easily into the surrounding Franciscan church complex. But step inside, and the world shifts. Thousands of human bones line the walls and columns, arranged in careful symmetry. Skulls stare back at you, unblinking.

It’s not horror that fills the room—it’s humility. Built in the late 16th century by Franciscan monks, the chapel was never meant to shock. It was meant to remind. To invite every visitor to pause and ask: what truly matters, when all of this—flesh, ambition, possessions—inevitably falls away?

A City Shaped by Time

Évora is one of Portugal’s oldest and most atmospheric cities, a UNESCO World Heritage site filled with cobbled streets, Roman ruins, and whitewashed houses edged in yellow. The city’s layered past—Roman, Moorish, medieval—can be read in its walls. Amid this historic calm, the Chapel of Bones offers something rare: not just beauty, but reflection.

The Franciscan friars who built it were responding to a very practical problem. In the 1500s, Évora had dozens of cemeteries taking up valuable land within the city walls. The friars decided to exhume the bones, but instead of hiding them away, they used them to build this chapel inside the Church of São Francisco.

Their message is written above the entrance:

“Nós ossos que aqui estamos pelos vossos esperamos.”

“We bones that are here, await yours.”

It’s haunting, yes—but also deeply human.

Inside the Chapel: Silence and Light

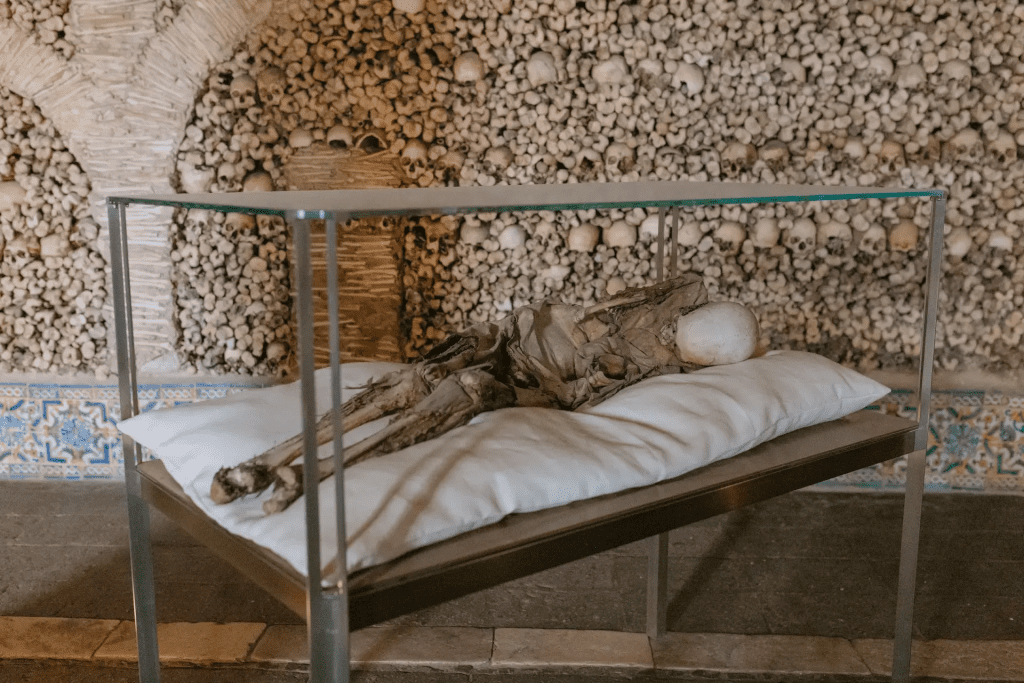

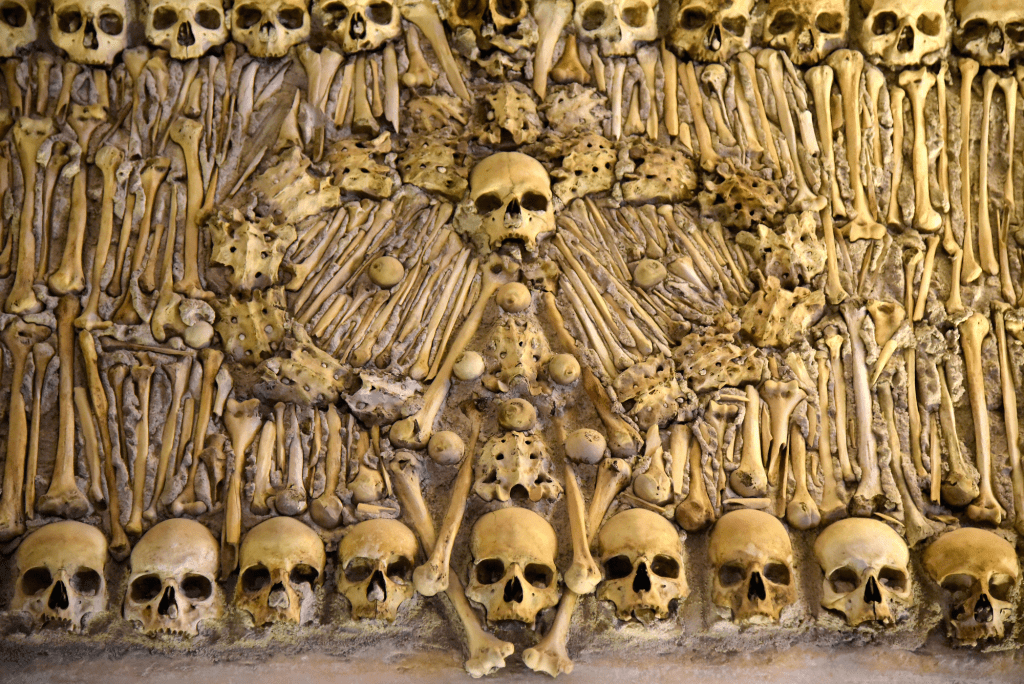

The Chapel of Bones is small—about 18 by 11 metres—but every inch tells a story. Around five thousand skeletons are believed to have been used in its construction. The bones are arranged in intricate patterns across the walls and columns, creating an oddly harmonious rhythm between life and death.

Natural light filters through narrow windows, casting soft beams over the skulls. The air is cool and still. It’s a place that demands quiet, not out of fear, but reverence.

Look up, and you’ll find a vaulted ceiling covered in painted motifs and Latin inscriptions. One reads: “Melior est dies mortis die nativitatis”—“Better is the day of death than the day of birth.”

In a small side alcove, two mummified bodies hang—once thought to be a man and his son, now known to be a woman and child. Their presence is unsettling but strangely peaceful, another layer in the chapel’s meditation on impermanence.

The Meaning Behind the Bones

It’s easy to see the Chapel of Bones as a macabre curiosity. But that’s not what it was meant to be. The Franciscans built it as a sermon in stone—an architectural reflection on the fleeting nature of human existence.

During the 16th century, Europe was steeped in religious reform and reflection. The monks believed that by confronting death visually, people might live more mindfully, embracing humility, compassion, and faith.

The bones here came from ordinary citizens—peasants, monks, townspeople. No names, no markers, no distinctions. In death, they became equal. That message still resonates today, even in a secular world where we often avoid thinking about mortality.

The chapel doesn’t ask you to be afraid. It asks you to be present.

Art, Order, and the Unexpected Beauty of Death

What surprises many visitors is how strangely beautiful the Chapel of Bones is. The repetition of shapes, the golden tones of the aged bones, the symmetrical arches—they all create a visual harmony that softens the horror. It’s art born from the inevitable.

There’s a rhythm here: the rounded skulls, the long bones stacked like cathedral bricks. Even the plaster between them has a painter’s precision. The monks arranged the bones not randomly but intentionally, transforming what could have been gruesome into something contemplative.

That balance—between the sacred and the unsettling—is what gives the Chapel its power. It doesn’t glorify death; it honours the life that once filled these bones.

Beyond the Chapel: The Church of São Francisco

The chapel is part of the larger Igreja de São Francisco, one of Évora’s grandest churches. The contrast between the two is striking. The church, with its high ceilings and ornate altars, celebrates divine glory. The chapel, humble and bone-clad, reminds us of human fragility.

Together, they embody a spiritual balance—heaven and earth, grandeur and decay, eternity and dust.

Visiting the Chapel of Bones

If you visit Évora, give yourself time. The chapel is small but best experienced slowly. Here’s what to know before you go:

Location: Rua da República, inside the Church of São Francisco complex, Évora.

Opening hours: Usually from 9 am to 5 pm (longer in summer).

Entry fee: Around €5, including access to the museum.

Photography: Allowed, but please be discreet and respectful.

Arrive early or just before closing to avoid crowds. The space loses much of its atmosphere when filled with people. Step inside quietly, and let your eyes adjust to the dim light.

Afterwards, wander through Évora’s narrow lanes, find a café under the Roman Temple’s shadow, and sit with what you’ve just seen. The contrast between sunlight and skulls lingers in a way you don’t forget.

Nearby Places to Explore

Évora’s beauty doesn’t stop at the chapel’s doors. Around the historic centre, you’ll find a blend of eras and influences that make it one of Portugal’s most captivating small cities.

Templo Romano de Évora (Roman Temple): Ancient granite columns from the first century, once dedicated to Emperor Augustus.

Évora Cathedral (Sé de Évora): A fortress-like Gothic cathedral with panoramic views from its rooftop.

Praça do Giraldo: The city’s central square, lined with cafés and fountains—perfect for people-watching.

University of Évora: Founded in 1559, its cloisters and azulejos (tiles) are worth exploring.

Local restaurants: Try açorda alentejana (bread soup with garlic and poached egg) or porco preto (black pork) paired with a regional wine.

For a slower pace, head beyond the city walls. The Alentejo countryside is a world of cork forests, olive groves, and white villages under vast skies.

Reflecting on the Experience

Here’s what makes the Chapel of Bones unforgettable: it’s not about death. It’s about life—and how we choose to spend it. Standing in that dim chapel, surrounded by thousands of anonymous souls, you can’t help but sense perspective returning.

The monks who built it believed that facing mortality could make us more alive, more grateful, more compassionate. Maybe that’s what we need now, in an age obsessed with youth and permanence: a quiet place that whispers, “remember to live.”

Travel is full of moments like that—small encounters that shake something loose inside you. The Chapel of Bones is one of them.

Practical Travel Notes

Best times to visit: Spring and autumn for mild weather; Évora can be very hot in summer.

Stay overnight: The Pousada Convento de Évora, a former 15th-century convent, is right beside the Roman Temple and offers an unforgettable setting.

Getting there: Évora is about 90 minutes by train or car from Lisbon. Buses run frequently too.

Dress respectfully: Shoulders covered, quiet tone—it’s still a sacred space.

A Final Word

The Capela dos Ossos isn’t for everyone. But for those open to it, it leaves a mark far deeper than most monuments. It asks a timeless question—what will we leave behind?

Perhaps that’s why, despite its eerie appearance, many leave smiling softly, thoughtful, even grateful. The bones may be silent, but they speak clearly: life is brief. Make it count.