Portugal, for such a tiny nation, definitely dazzles in its different forms and manifestations. From the sun-drenched beaches and plains of the south to the hilly areas and lush green hills of the north, there is something for everyone. Portugal’s amazing diversity of scenery is matched by the country’s many attractive towns and majestic cities. From UNESCO-listed monuments to border communities, stunning hilltop villages, and sophisticated metropolises, each has its own distinct Portuguese personality and charm.

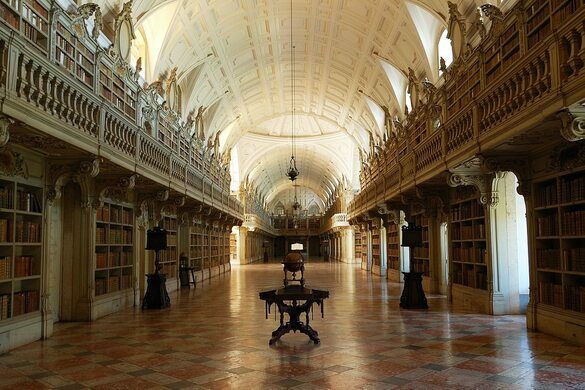

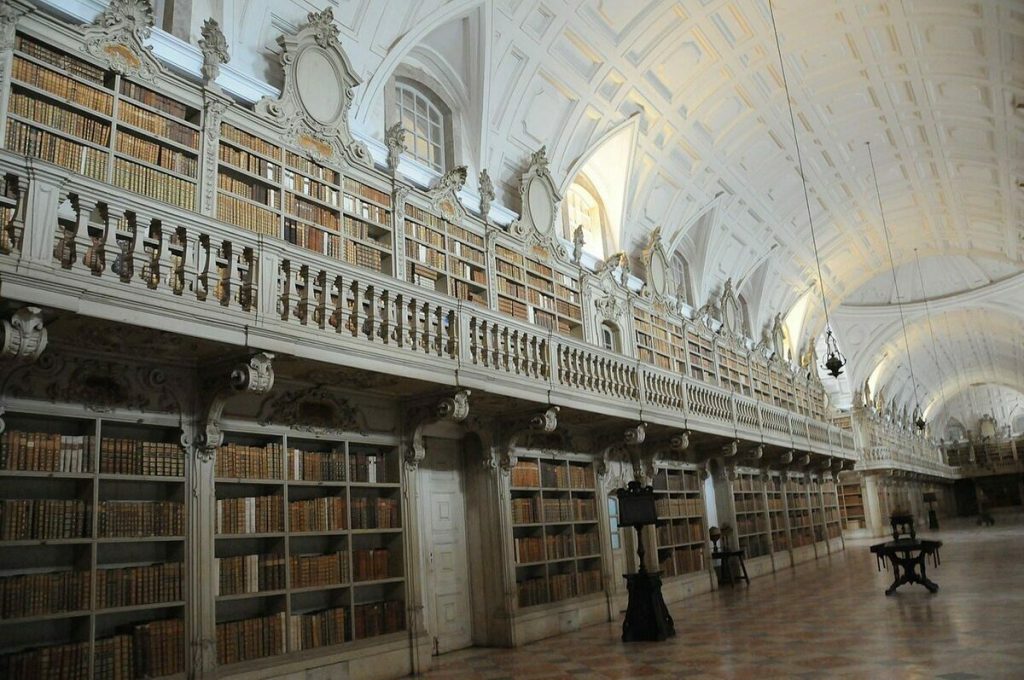

Mafra Palace Library,Portugal

Mafra is a city and a municipality in the district of Lisbon, on the west coast of Portugal

THE GRAND MAFRA PALACE LIBRARY’S WOODEN ROCOCO BOOKSHELVES STORE ABOUT 36,000 leather-bound books ranging from the 14th to the 19th centuries. If not for the inch-long bats that monitor the library at night, book-eating bugs would represent a serious danger to these ancient tomes.

When the majestic Palace of Mafra was completed in 1755, it quickly established itself as a national treasure of Portuguese architecture. Additionally, the palace has an equally magnificent library, one of the best in Europe.

The 280-foot-long Rococo-style library is an appropriate setting for the thousands of priceless antique volumes that fill the wooden bookcases. However, these books are delicate, and bookworms, moths, and other insects may wreak havoc on their fragile pages.

The majority of libraries use ethylene oxide, methyl bromide, or gamma radiation to combat such pests, however, the Mafra Palace Library has a rather unique army of aerial defenders: bats.

During the day, a colony of bats naps beneath the bookshelves or in the garden of the castle. At night, after the library has closed, these tiny bats fly between the stacks, searching for the bugs that would otherwise chew through the library’s priceless collection of books.

This midnight feasting has existed for ages, perhaps dating all the way back to the invention of the library. However, the winged guardians do have one disadvantage: the enormous amount of droppings they deposit on the floors, shelves, and furniture each night. To counteract this, library staff covers furniture before they leave and spends their mornings meticulously washing the marble floors to remove any traces of the previous night’s excrement.

According to the palace website, the Mafra Palace Library is accessible to researchers, historians, and academics “whose subject of study warrants access to this collection.” It is suggested that you make an appointment in advance. Because bats are nocturnal, it is doubtful that you will encounter them during visiting hours. Monday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday from 9:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. and 2:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m.

Chapel of Nossa Senhora das Vitórias

São Miguel Island, Azores

This fairy-tale, neo-Gothic church in the Azores is a world of magical realism.

Lagoa das Furnas: Ermida do Canto

The Chapel of Our Lady of Victories, Capella de Nossa Senhora das Vitórias, was dedicated to Maria Guilhermina Taveira de Brum da Silveira, the wife of a local landowner called José Do Conto. She had sadly succumbed to severe illness, and her husband took it upon himself to build this enchanting lakeside church. By using his famous design and gardening abilities, despite the structural aspects, the whole effort seems more magical realism-inspired than hard-edged gothic.

Do Conto did not complete the piece personally but compelled it to be completed before his death in 1898. He lived to see it completed, and his desire to be buried beside his wife was granted; both are buried in the Chapel. There are 18 windows, the majority of which are filled with vibrant stained glass, which illuminates the couple’s last resting place with vibrant gospel images.

There are no religious services performed here, giving the area an old, abandoned, and even timeless air as the natural elements take control. It resembles an ancient tree, deeply planted and ingrained in the forest. It stands out as one of the most charming and rustic locations in the Azores due to the Chapel, the gardens, the lake, and the surrounding mountains.

It’s approximately a four-mile drive south on EN1-1A from the town centre of Furnas. Just beyond the lake on your right, bear right onto the gravel road marked with lake signs. The Chapel is located about a quarter-mile down the road, just across from Lagoa das Furnas.

While almost every stroll around the lake provides views of the Chapel, for a closer look (and maybe a peep inside), visitors can spend a few euros for entry to the adjacent José do Canto Forest Garden. You may access the Chapel and its gardens directly, as well as waterfalls, art pieces, and other abandoned buildings strewn around the Chapel’s backyard’s meandering pathways.

Cemetery of Anchors

Santa Luzia, Portugal

No one knows who set the first of the hundreds of rusty anchors strewn over the sand dunes of Praia do Barril Beach. Locals, though, continued to add the gnarled weights to commemorate the tiny tuna fishing community that previously thrived in the region.

The anchors were used to weigh down the nets that were used to capture tuna. They are arranged in rows and exist without any real grandeur or formality. The unstable seas where the Atlantic met the Mediterranean were teeming with bluefin tuna, making fishing in the region a hazardous and challenging vocation. The method of capturing them was unique to the region and was most likely developed by the ancient Romans who occupied there.

The island and Barril Beach are accessible from the town of Santa Luzia via a bridge and a 1.2km walk. Alternatively, there is a small railway along 1km of the line (which was formerly used by the fishing community to carry products and freshly caught fish) that runs a mini-train at peak hours

Ponte da Misarela (Misalera Bridge)

Montalegre, Portugal

In northern Portugal, a medieval stone bridge arcs above the Rio Rabago.

According to local legend, a criminal was fleeing the neighbouring hamlet and needed the means to cross the river. He called the devil, who graciously agreed to assist the guy for the modest price of his soul. The guy consented, and the devil built a makeshift bridge that disappeared before the convict’s pursuers could cross.

According to legend, the bandit was so repentant that he sought out a priest to confess his sins. A good priest saw the man’s plight and used his Rosary and a little amount of holy water to banish the demon and transform the bridge into a permanent construction.

Visitors to the Misarela Bridge today won’t have to worry about it disappearing under their feet. Anyone may stroll (or escape, if necessary) over the river thanks to the strong stones. In reality, during the Peninsular War in the early 1800s, French soldiers used the bridge to escape British forces.

Take in the sights of the surrounding environment while you’re there. The area is filled with trees and plants, its green cover spreading down the slope till it reaches the water and rocks. You’ll most certainly see a waterfall pouring over the rocks near the bridge after a rainstorm. In the summer, visitors may cool themselves in the river below.

Anta de Pavia, Portugal

Pagan monument converted to Christianity with the population.

THE ANTA DE PAVIA STANDS OUT EVEN WITHOUT ITS HISTORY. A massive rock has remained in the middle of a plaza in Pavia for generations, surrounded by white-washed, red-roofed houses.

The 4 meters high stone, which was once a dolmen, was used as a burial chamber when paganism went out of favour. When Christianity replaced most other faiths in the 17th century, the huge rock was renamed a tiny church dedicated to São Dinis. The inner chamber of the dolmen was converted into the chapel’s nave, and although it is still sparse, it has a tiny blue-tiled altar.

While the chapel is an intriguing landmark, it is much more so since it recounts a typical narrative of medieval Portugal’s conversion, and numerous similarly converted pagan buildings can be seen across the nation.

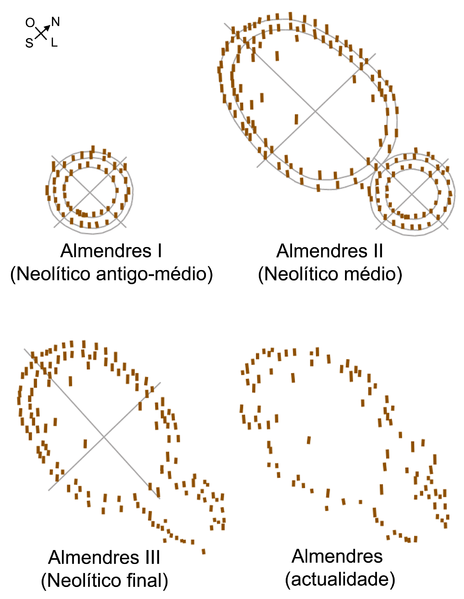

Almendres Cromlech

Évora, Portugal

“Portugal’s Stonehenge” is made up of nut-like stones aligned with the heavens.

The Almendres Cromlech are the best example of Neolithic buildings on the Iberian Peninsula, built over many periods between 5000 and 4000 BCE and being undiscovered until 1966.

Several typical megalithic monuments, mainly cromlechs and menhir stones, may be seen at the site. The 95 almond-shaped stones visible today are arranged in patterns of two concentric rings – an eastern circle and a bigger oval in the west – and reflect a steady process of collection and redistribution through time.

The site’s earliest part is the smaller ring to the east, created during the early Neolithic period about 6000 BCE, while the western oval ring is believed to have been erected during the Almendres era around 5000 BCE. Many of the stones seem to have been moved during a third phase about 3000 BCE to better coincide with the moon, sun, and stars.

The function of Almendres Cromlech is unclear, as is typical of such ancient structures. The final repositioning of the stones to align with celestial bodies reinforced geometric patterns previously discovered at Almendres Cromlech, making the intentionality of the stones’ existence and placement undeniable, even if the deeper reasoning and rites contained within remain a mystery.

There are no public transportation alternatives, and the stones are located distant from main highways.

East of Evora, right off the major N114 road that links Evora to Montemor-o-Novo.

The entire journey from the outskirts of Evora to the ancient site is 16km (10miles) and takes around 25 minutes.

Espigueiros do Soajo, Portugal

A cluster of granite granaries perched on stilts.

The ancient hamlet of Soajo is located on the outskirts of the magnificent Peneda-Gerês National Park in Portugal. Its beautiful homes and tiny church add to the scene, but it is most renowned for its magnificent espigueiros: granite granaries constructed above ground.

The name Espigueiros refers to the granaries, which are supported by granite slabs from the Peneda mountains. They were raised above the ground to protect food crops from rats and other vermin, and the whole community utilized them.

The first espigueiros were built in 1782, and the whole cluster was built during the 18th and 19th centuries. Some of the 24 that remain are still used to store grain, particularly maize.

These traditional granaries may also be seen in the hamlet of Lindoso, which is just 6 miles (10 kilometres) from Soajo. There are more than 50 of them, and they are still used to store grain collected by villagers.

From Porto Airport, take the A3 highway to Braga/Valença. After 47 miles (77 kilometres), exit the highway at the Arcos de Valdevez exit. After paying the toll, continue on the IC28 for 9 miles (15 kilometres) and exit at Arcos de Valdevez. At the town’s entrance, there is a roundabout labelled “Soajo/Mezio/PNPG.” Take the signs to “Soajo/Mezio.” After 1.8 miles (3 kilometres), turn right in the direction of “Soajo/Mezio” and continue for 11 miles (18 kilometres) until you reach the hamlet of Soajo.

Capela do Senhor da Pedra

Arcozelo, Portugal

The stunning marble- and granite-strewn beaches of Miramar were originally the SITE site of ancient pagan worship. The Capela do Senhor da Pedra (Chapel of the Lord of Stone) stands now on top of a massive rock protruding into the sea, where rites were previously conducted.

During the 17th century, the hexagonal building was built as part of a major effort to Christianize Europe in order to ‘reclaim’ the country from the ‘heretic,’ naturalist pagans who sought enlightenment at the same location.

Visitors may either climb the set of steps going from the beach to the altar or follow the more penitent path up the steep rocky slopes. The sanctuary doors are bordered by two azulejo mosaics that flaunt the site’s architectural significance while also mentioning that Pagans worshipped here before the chapel became “surely the oldest house of worship in the area.” Inside, three magnificent gold-leaf altars portraying Christ hanging on the cross were built. The crucifix is now backlit by a (controversial) green light.

A horseshoe-shaped indent in the rock appears at the back of the chapel. Explanations for its origin are strange and hazy, ranging from belonging to the Virgin Mary’s donkey to having roots in D. Sebastian’s horse that was badly managed on a misty day, and so on.

Perhaps most intriguingly, an annual three-day celebration honouring the site’s Pagan history takes place in Miramar beginning on Trinity Sunday. The celebrations climax the following Tuesday with a march from the city centre to the church headed by completely veiled ladies (“witches whose identities remain unknown,” according to one local).

The church is worth seeing not just for its unusual setting and breathtaking views, but also for its representation of a cultural conflict whose remnants may still be seen today.

Travel south by rail from Porto/Vila Nova do Gaia. Exit the station at Miramar and go towards the sea, which will be clearly visible.

Covão dos Conchos, Portugal

Despite its surreal appearance, the hole in Portugal’s Lagoa da Serra da Estrela is really a man-made funnel leading into a long tunnel. Though it seems to be a natural sinkhole surrounded by flowing waterfalls, Covo dos Conchos is an engineering marvel.

This lake in the Serra da Estrela mountains was constructed artificially in 1955 as part of the adjacent hydroelectric project development. Rather than construct a pipeline to link Lagoa Serra da Estrela and Lagoa Comprida, the project’s engineers chose to dig a tunnel through the mountain.

The spillway is intended to provide fresh water to surrounding towns, but the lack of other structures nearby gives the funnel the appearance of being a natural feature of the lake rather than an engineering project. Additionally, plants are growing along the sides of the concrete and granite drain pipe, giving the massive hole an even more natural appearance. Until pictures of the hole went viral in 2016, this sci-fi-looking spillway was a little-known mystery in Portugal.

Covo dos Conchos is situated in the natural park of Serra da Estrela, which is far from any major city. The trail to the spillway begins at Lake Comprida and is about 6 miles (10 kilometres) in length. Bring lots of water and sturdy shoes.

Pego do Inferno

The name Pego do Inferno, which translates as ‘Pit of Hell,’ refers to a beautiful waterfall and lagoon created by the Asseca stream.

This beautiful location, situated in Santo Estêvo, Tavira, is a real hidden treasure.

The area around Pego do Inferno is very lovely, and it’s worth visiting for the view alone. The journey to Pego do Inferno is scenic, as you are surrounded by orange and lemon trees, and the landscape provides for a delightful stroll on a bright day, as well as a pleasant day out in general.

To reach the waterfall, it is well concealed and not the simplest way to take due to the unmarked trails, but for explorers, it provides for an intriguing route to pursue but one that should be taken with care. The lovely cascade is fed by the Asseca River and winds its way over limestone cliffs that create an enchanting lagoon. Calcium carbonate removed from the rock accumulates in the lagoon, imparting a magnificent green hue to the water. The Pego do Inferno waterfall is the biggest of three in the Cascade da Torre and Cascade of Pomarinho series.

With a height of just 3 metres, this waterfall is on the smaller side. Additionally, to pique interest and spice up the visit a little, the Waterfall of Pego do Inferno is linked with a scary tale. According to folklore, a wagon collapsed at Pego, plunging the passengers into the lagoon. The divers were never able to locate the bodies of the wagon’s passengers or the animals that hauled it. Because the divers were unable to reach the lagoon’s bottom, they concluded that the victims had plunged into hell. Thus, the eerie moniker Hell’s Pool/Pit of Hell was created. According to folklore, anybody who falls into it will immediately enter hell.

Casmilo Holes (Buracas the Casmilo)

The Buracas de Casmilo are an intriguing geological feature in the Portuguese municipality of Condeixa-a-Nova, Zambujal parish.

Casmilo is located on the route that links the hill of Senhora do Círculo to Serra de Janeanes. We arrive at Buracas do Casmilo after entering the village and following a route marked by the karst landscape of limestone.

This intriguing geological structure, surrounded by huge cliffs, relates to the remnants of many chambers of a cave that existed within the mound as a consequence of the lowering of the centre section of a pipeline, leaving its extreme lateral parts exposed.

Climbing, mountaineering, orienteering, rappelling, and camping are all popular outdoor activities in Buracas do Casmilo and its surrounding region.